Venturing into the great outdoors offers unparalleled experiences, but it also comes with inherent risks. When you’re miles from the nearest hospital, having the knowledge to handle medical emergencies can mean the difference between life and death. Whether you’re an occasional day hiker or a seasoned backpacker, emergency preparedness is a crucial aspect of outdoor safety that’s often overlooked. This article explores the essential CPR and emergency skills that every hiker should learn before hitting the trails, providing you with the confidence to respond effectively when accidents happen in remote locations.

Understanding the Importance of Wilderness First Aid

Wilderness first aid differs significantly from urban emergency response, primarily because professional medical help may be hours or even days away. In the backcountry, hikers must be prepared to provide extended care using limited resources until evacuation is possible. According to the National Park Service, response times for emergency services in wilderness areas average between 2-8 hours, compared to just minutes in urban settings. This substantial delay makes it essential for outdoor enthusiasts to possess basic medical knowledge and skills that can stabilize injured parties during the critical waiting period. Furthermore, environmental factors like extreme temperatures, difficult terrain, and wildlife encounters create unique challenges that aren’t typically addressed in standard first aid courses.

Essential Gear for Wilderness First Aid

Before learning emergency skills, hikers should assemble a comprehensive first aid kit tailored to wilderness adventures. Beyond basic supplies like bandages and antiseptic wipes, wilderness kits should include tools for immobilization (such as SAM splints), emergency shelter materials, and a method to communicate for help like a satellite messenger or personal locator beacon. Items specific to your hiking environment are also crucial—think blister treatment for long-distance trails, insect bite remedies for humid areas, or treatments for altitude sickness in mountainous regions. The American Hiking Society recommends that first aid supplies constitute approximately 10% of your pack weight on longer expeditions. Remember that even the most comprehensive kit is only as effective as your knowledge of how to use each item properly.

Recognizing and Responding to Cardiac Emergencies

Identifying the signs of a cardiac emergency quickly is paramount in wilderness settings where every minute counts. The primary indicators include chest pain or pressure, shortness of breath, nausea, light-headedness, and pain radiating to the jaw, shoulders, or arms. In remote locations, your immediate response should include having the person cease all activity, sit in a comfortable position, and take aspirin if available and not contraindicated by allergies or other conditions. Continually monitor the victim’s level of consciousness, breathing, and pulse while preparing for the possibility of CPR. The physical exertion of hiking, combined with potential altitude changes, can trigger cardiac events even in seemingly healthy individuals, making this knowledge essential for all wilderness travelers regardless of age or fitness level.

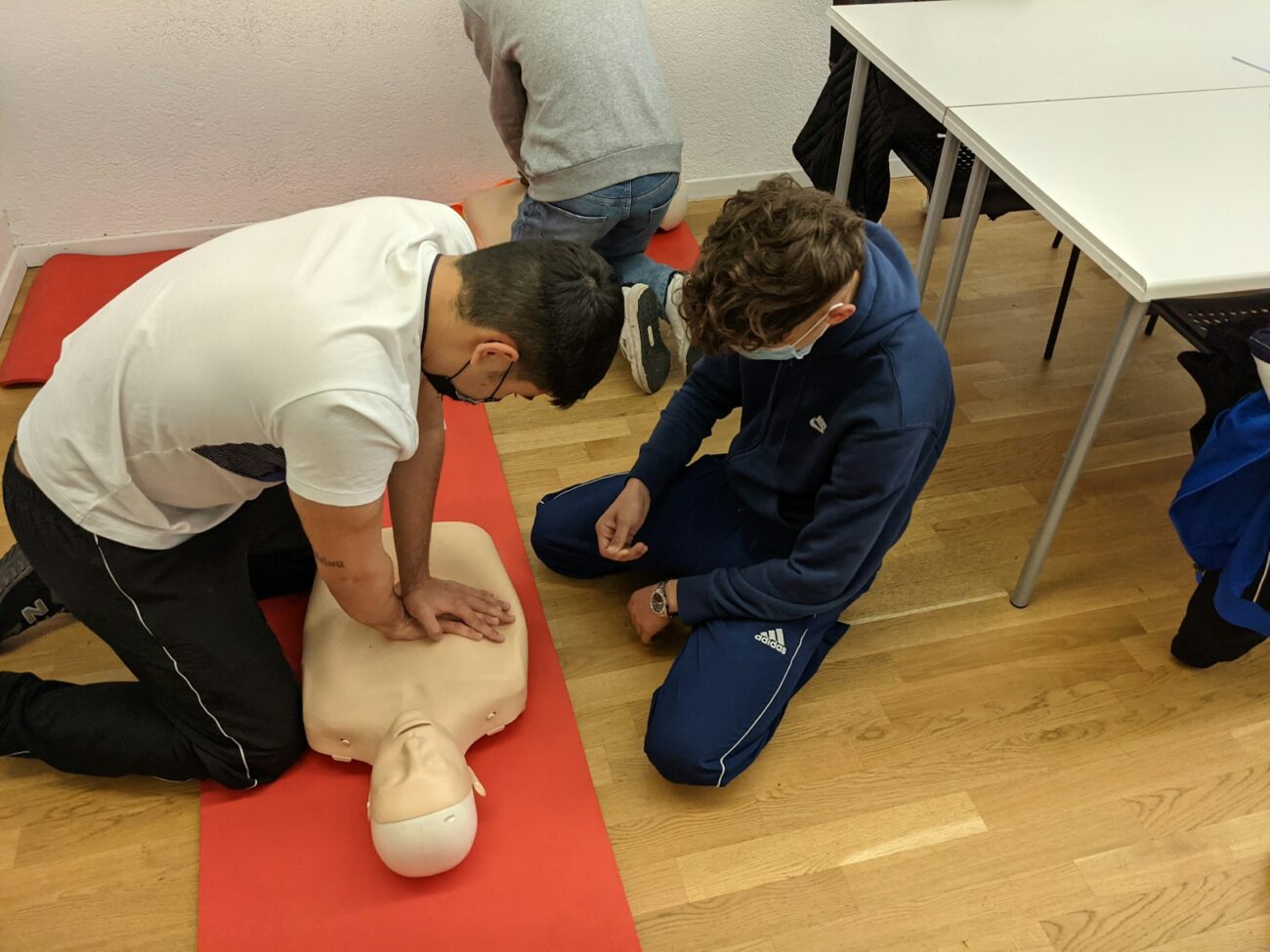

Performing CPR in Wilderness Settings

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the backcountry follows the same fundamental principles as conventional CPR but presents unique challenges. The current American Heart Association guidelines recommend hands-only CPR for untrained rescuers: push hard and fast in the center of the chest at a rate of 100-120 compressions per minute. In wilderness settings, however, you may need to perform CPR for extended periods while awaiting rescue, which can be physically exhausting—establish a rotation system if multiple trained people are present. Performing effective CPR on uneven terrain requires improvisation; consider placing your pack under the victim’s shoulders to create a firmer surface, or position them on a sleeping pad if available. Remember that wilderness CPR success rates are lower than in urban environments due to delayed response times, but documented cases of successful wilderness resuscitations make it a vital skill nonetheless.

Managing Severe Bleeding and Shock

Controlling severe bleeding quickly is one of the most critical wilderness first aid skills, as blood loss can become life-threatening within minutes. The modern approach prioritizes direct pressure and wound packing with gauze for deep wounds, followed by pressure bandages and elevation of the injured area when possible. Improvised tourniquets should only be used as a last resort for life-threatening bleeding from limbs that cannot be controlled by other means, as they can cause tissue damage if left in place too long. After addressing bleeding, preventing and treating shock becomes essential—lay the person flat, elevate their legs 8-12 inches if no spinal injury is suspected, insulate them from the ground, and keep them warm with extra clothing or emergency blankets. Monitoring vital signs is crucial, as a rapid pulse, shallow breathing, and decreasing alertness indicate worsening shock that requires urgent evacuation.

Handling Orthopedic Injuries on the Trail

Sprains, strains, dislocations, and fractures are among the most common injuries encountered during hiking adventures, often occurring on uneven or slippery terrain. The R.I.C.E. protocol (Rest, Ice, Compression, Elevation) provides the foundation for treating most orthopedic injuries, though ice may need to be improvised using cold water from streams or snow if available. For suspected fractures, immobilization is key—creating a splint from hiking poles, foam sleeping pads, or sturdy branches can prevent further damage during evacuation. When facing a potential dislocation, particularly of shoulders or fingers, wilderness medicine protocols sometimes recommend reduction (returning the joint to its proper position) in remote settings, though this should only be attempted by those with proper training. Understanding the difference between injuries you can safely manage with self-evacuation versus those requiring professional rescue is perhaps the most important judgment call you’ll make when dealing with orthopedic trauma in the backcountry.

Recognizing and Treating Heat Illnesses

Heat-related emergencies progress along a spectrum from mild heat cramps to potentially fatal heat stroke, with early recognition being crucial for effective treatment. Heat exhaustion presents as heavy sweating, weakness, dizziness, nausea, and headache—at this stage, moving the person to shade, removing excess clothing, and applying cool water to the skin while encouraging hydration with electrolyte-containing fluids can prevent progression. Heat stroke, characterized by altered mental status, cessation of sweating, and very high body temperature (above 104°F/40°C), represents a true medical emergency requiring immediate cooling through whatever means available—submerging in a cool stream, applying wet clothing, or fanning vigorously while evacuating. Prevention remains the best approach, with proper hydration (approximately 1 liter every 2 hours in hot conditions), appropriate clothing, and avoiding the hottest hours of the day for strenuous hiking being essential strategies for all wilderness travelers.

Identifying and Managing Hypothermia

Hypothermia can occur in any season when conditions combine to lower body temperature below normal, making it a year-round concern for hikers. Early signs include uncontrollable shivering, clumsiness, and poor decision-making, while advanced hypothermia manifests as slurred speech, unusual behavior, and eventually cessation of shivering—a particularly dangerous sign. The treatment approach follows the “rewarm and dry” principle: remove wet clothing, provide insulation with dry layers and emergency blankets, and add heat to the core body areas (neck, chest, armpits, and groin) using chemical heat packs or hot water bottles if available. In mild cases, having the person consume warm, sweet drinks can help raise core temperature, though never give drinks to someone with decreased consciousness. The often-overlooked aspect of hypothermia prevention includes proper nutrition, as your body requires adequate calories to maintain temperature in cold environments—experienced winter hikers often consume 30-50% more calories than in temperate conditions.

Managing Allergic Reactions and Anaphylaxis

Severe allergic reactions can occur in response to insect stings, plant contact, or food consumed during hiking trips, with potentially rapid progression to life-threatening anaphylaxis. The telltale signs include hives, facial or throat swelling, difficulty breathing, dizziness, and a sense of impending doom. For hikers with known severe allergies, carrying epinephrine auto-injectors (such as EpiPen) is essential, and all group members should know their location and proper use. For those without prescribed medication, antihistamines like diphenhydramine (Benadryl) can help manage mild to moderate reactions, though they won’t reverse anaphylaxis. After administering emergency medication, rapid evacuation remains crucial, as epinephrine effects are temporary and symptoms may return. Prevention strategies include researching potential allergens specific to your hiking area, such as particular plants, insects, or marine life for coastal trails.

Snake Bites and Other Wildlife Encounters

Venomous snake encounters, while relatively rare, require specific knowledge that contradicts outdated first aid approaches. The current protocol for snakebites emphasizes keeping the victim calm, removing constrictive items like watches or rings before swelling occurs, immobilizing the affected limb at or below heart level, and evacuating immediately—specifically avoiding outdated techniques like suction, cutting, tourniquets, or ice application, which can worsen outcomes. For other wildlife encounters resulting in injury, wound cleansing is paramount due to the high infection risk associated with animal bites. Bear attacks, though extremely uncommon, require different responses depending on the species: playing dead may be effective with defensive grizzly bears, while fighting back is recommended for black bear attacks. Understanding the wildlife specific to your hiking region and carrying appropriate deterrents, such as bear spray in certain areas, forms an essential part of wilderness emergency preparedness.

Emergency Navigation and Signaling

When medical emergencies occur in remote areas, the ability to communicate your location precisely to rescue services becomes as important as the first aid provided. Every hiker should carry multiple navigation tools—maps, compass, and GPS or smartphone apps—and know how to use them to determine and communicate coordinates during emergencies. For signaling, carrying a whistle (the international distress signal is three short blasts) and a mirror for reflecting sunlight can attract attention from considerable distances. More advanced options include personal locator beacons (PLBs) or satellite messengers that can transmit your exact location to emergency services with the push of a button. When possible, sending your most physically capable group members to seek help while others remain with the injured person is often the most efficient approach, ensuring those going for help have clear information about the location, nature of injuries, and resources remaining with the patient.

Evacuation Decision-Making

Perhaps the most challenging aspect of wilderness emergency management is determining when and how to evacuate an injured hiker. Self-evacuation may be appropriate for stable injuries like simple sprains or minor illnesses when the patient can move safely with assistance. However, conditions including altered mental status, breathing difficulties, severe bleeding, suspected spinal injuries, or worsening symptoms generally warrant professional evacuation. The decision framework should consider the severity of the injury, distance from help, available resources, terrain challenges, weather conditions, and time of day. Improvised stretchers can be constructed using trekking poles through jacket sleeves or with a tarp wrapped around sturdy branches, though moving an injured person over rough terrain requires significant manpower and technical skill. When professional rescue is needed, preparing a suitable landing zone for helicopter evacuation by clearing loose objects and marking the area with bright clothing can expedite the process.

Training and Certification Options

While reading about emergency skills provides a foundation, hands-on training offers incomparable preparation for real-world scenarios. Wilderness First Aid (WFA) certification courses, typically 16-20 hours in duration, provide an excellent starting point for recreational hikers, covering the fundamentals of emergency care in remote settings. For those who frequently lead groups or venture into very remote areas, the more comprehensive Wilderness First Responder (WFR) certification, involving approximately 70-80 hours of training, offers in-depth knowledge of extended care protocols. Organizations like NOLS (National Outdoor Leadership School), SOLO (Stonehearth Open Learning Opportunities), and the American Red Cross offer wilderness-specific medical training throughout the country. Many outdoor clubs and hiking organizations also host shorter skills workshops focusing on specific emergency techniques, providing accessible entry points for those unable to commit to full certification courses.

The wilderness offers unparalleled beauty and adventure, but its remoteness creates unique challenges during medical emergencies. By investing time in learning these essential emergency skills, hikers not only protect themselves but also become valuable resources for fellow outdoor enthusiasts in need. Remember that these skills require regular practice and periodic refresher training to maintain proficiency. As the outdoor community often says, the best emergency is the one prevented—so while developing these critical response capabilities, continue to hike within your limits, prepare thoroughly, and make conservative decisions when faced with changing conditions. The wilderness will always contain inherent risks, but with proper preparation, you can venture forth with confidence in your ability to handle unexpected situations effectively.