When visiting parks, zoos, or natural habitats, it’s common to see signs warning visitors not to feed the wildlife. Despite these clear instructions, many people still offer food to wild animals, believing they’re being kind or helpful. This seemingly innocent gesture, however, can have devastating consequences for animal health, behavior, and entire ecosystems. The practice of feeding wild animals represents one of the most significant yet underappreciated threats to wildlife conservation efforts worldwide.

Understanding why feeding wildlife is dangerous requires examining its wide-ranging impacts on animal health, behavior, and the delicate balance of natural environments.

The Natural Diet Disruption

Wild animals have evolved over thousands of years to consume specific foods available in their natural habitats. When humans introduce processed, high-calorie, or nutritionally inadequate foods, animals suffer from significant dietary imbalances. For example, bread commonly fed to ducks and geese lacks essential nutrients and can cause a condition called “angel wing,” a wing deformity that prevents birds from flying properly. Similarly, deer fed corn in winter can develop acidosis, a potentially fatal condition resulting from the sudden introduction of foods their digestive systems aren’t prepared to process.

Even foods that seem appropriate, like nuts for squirrels, can disrupt natural foraging behaviors and create unhealthy dependencies when provided in excessive amounts or outside of natural seasonal patterns.

Dependency and Loss of Self-Sufficiency

Regular feeding creates dangerous dependencies that compromise animals’ natural survival skills. When wildlife begins to associate humans with food, they gradually lose their ability and motivation to forage or hunt independently. Young animals particularly suffer as they fail to develop critical survival skills when raised in environments where food is artificially provided. This dependency becomes especially dangerous during seasonal changes when human visitors decrease but animals remain reliant on handouts. In national parks like Yellowstone, bears that become food-conditioned often face euthanasia because they’ve lost their natural foraging abilities and become potentially dangerous to humans.

The transition back to natural feeding behaviors is often impossible once these dependencies form, creating a permanent vulnerability for affected animals.

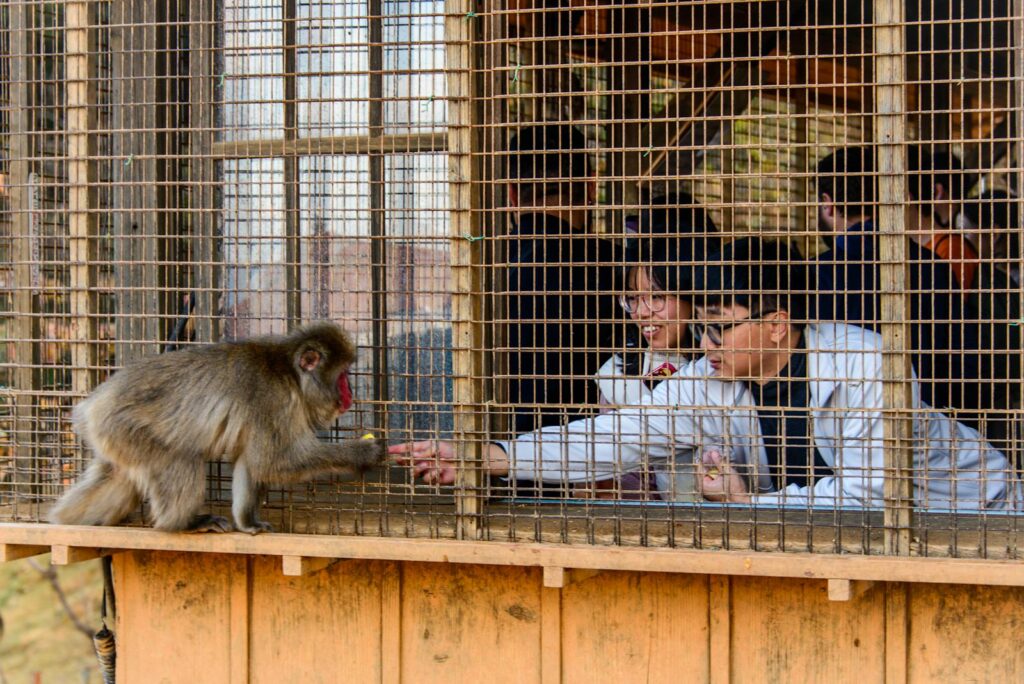

Dangerous Human Habituation

Wildlife that associates humans with food loses their natural and healthy fear of people, leading to problematic habituation. This habituation increases potentially dangerous animal-human encounters, particularly with species like bears, coyotes, or alligators that may become aggressive when seeking food. In suburban areas across North America, habituated deer increasingly approach humans for food, leading to attacks during rutting season or when females protect fawns. Even smaller animals like raccoons or squirrels can deliver painful bites or scratches when food isn’t offered as expected.

Wildlife managers often summarize this phenomenon with the grim phrase “a fed animal is a dead animal,” reflecting the reality that habituated wildlife frequently must be euthanized after aggressive encounters with humans.

Disease Transmission Risks

Feeding wildlife creates unnatural congregations of animals, dramatically increasing disease transmission opportunities. When multiple animals gather at feeding sites, pathogens spread rapidly through direct contact, shared food sources, or contaminated areas. Chronic Wasting Disease in deer populations, for example, spreads more quickly when deer congregate at artificial feeding sites. Bird feeders, when not regularly cleaned, can transmit deadly diseases like salmonellosis, avian pox, or conjunctivitis among songbird populations. Additionally, close contact between different species that wouldn’t normally interact can create new pathways for zoonotic diseases to emerge and spread.

These disease risks extend to humans as well, with increased possibilities for transmission of diseases like rabies, leptospirosis, or various parasites when people interact closely with wild animals.

Population Imbalances

Artificial feeding disrupts natural population controls by providing resources that allow certain species to reproduce beyond their habitat’s natural carrying capacity. This artificial abundance creates unsustainable population booms that eventually lead to resource depletion, increased competition, and widespread suffering when the artificial food source disappears. In urban areas, feeding pigeons or gulls has led to population explosions that damage infrastructure, create public health hazards, and displace native bird species. Similarly, feeding deer in suburban areas has contributed to overpopulation that devastates forest understories, eliminates habitat for other wildlife, and increases deer-vehicle collisions.

These artificially supported populations often collapse catastrophically when feeding stops, resulting in mass starvation rather than the gradual population adjustments that occur in balanced ecosystems.

Ecosystem Disruption

Feeding wildlife doesn’t just affect individual animals—it can destabilize entire ecosystems by artificially favoring certain species over others. When raccoons, squirrels, or other adaptable omnivores receive supplemental food, they often experience population booms that increase predation pressure on vulnerable species like songbirds, amphibians, or native small mammals. In marine environments, feeding fish disrupts natural foraging patterns and alters reef ecology by concentrating certain species in artificial feeding zones. Even seemingly positive interventions, like winter bird feeding, can have unintended consequences by supporting invasive species or changing migration patterns.

These ripple effects often extend far beyond the feeding site, altering predator-prey relationships and competitive dynamics across the broader ecosystem in ways that can persist for generations.

Environmental Contamination

Food waste from wildlife feeding creates significant environmental contamination issues in natural areas. Uneaten food attracts pests like rats and insects, creating secondary nuisance wildlife problems in parks and natural areas. In aquatic environments, excess food decomposes and reduces water quality through nutrient loading, potentially causing harmful algal blooms that deplete oxygen and kill fish. Even biodegradable foods like bread or fruit can alter soil chemistry and promote the growth of non-native plant species when concentrated in specific areas.

The cumulative impact of thousands of visitors leaving small amounts of food creates persistent environmental degradation in popular wildlife viewing areas, affecting not just the fed animals but all species that depend on that habitat.

Migration Pattern Disruption

Artificial feeding sites can severely disrupt critical migration patterns that wildlife has developed over thousands of years. When migratory birds find reliable food sources from humans, some individuals may delay or completely skip seasonal migrations, putting them at risk during harsh weather conditions they’re not adapted to endure. In areas like the American Southwest, fed hummingbirds sometimes delay migration with fatal consequences when sudden cold snaps arrive. Similarly, waterfowl that remain in northern regions due to artificial feeding often suffer frostbite and freezing when temperatures plummet.

These disruptions can have population-level impacts by altering breeding cycles, separating mated pairs, and creating genetic isolation between populations that would normally interbreed during migrations.

Nutritional Deficiencies and Health Problems

Even well-intentioned feeding often provides wildlife with nutritionally inadequate foods that lead to serious health problems. White-tailed deer fed corn during winter can develop potentially fatal conditions like acidosis and enterotoxemia because their digestive systems are adapted for woody browse during cold months, not high-carbohydrate foods. Waterbirds like swans and ducks develop wing deformities and metabolic bone disease when raised on bread-heavy diets lacking essential nutrients. Calcium deficiencies are particularly common in fed wildlife, leading to weakened bones, eggshell problems, and reproductive failures.

These nutritional issues often remain invisible to casual observers until they become severe, giving feeders a false impression that they’re helping animals that are actually suffering from their interventions.

Behavioral Changes and Social Disruption

Feeding wildlife fundamentally alters natural social structures and behaviors that have evolved over millennia. In species with complex social hierarchies like wolves or primates, artificial feeding sites create abnormal competition that can disrupt pack or troop dynamics. Young animals fail to learn proper social behaviors when their interactions center around competing for artificial food sources rather than natural cooperative behaviors.

Feeding can also disrupt parental care patterns, with some species abandoning normal nurturing behaviors when food is easily available. In bears, artificial food sources have been documented changing denning behaviors and cub-rearing practices, with potentially long-term impacts on population health and stability.

Legal Consequences

Many people don’t realize that feeding wildlife is illegal in numerous jurisdictions, carrying significant legal penalties. National parks throughout the United States strictly prohibit wildlife feeding, with fines ranging from hundreds to thousands of dollars for violations. In Florida, feeding alligators is a serious offense carrying potential jail time because of the extreme danger created by habituated alligators. Many states have enacted specific regulations against feeding deer and other game animals due to disease concerns, with penalties including substantial fines and loss of hunting privileges.

Even feeding smaller animals like squirrels or birds is prohibited in many city parks and natural areas, with enforcement becoming increasingly stringent as awareness of ecological impacts grows.

Responsible Wildlife Viewing Alternatives

Fortunately, there are many ways to connect with wildlife without the harmful effects of feeding. Wildlife photography offers a non-disruptive way to appreciate animals while creating lasting memories and potentially beautiful art. Participating in citizen science programs like bird counts or wildlife surveys allows meaningful engagement with nature while contributing to conservation efforts. Creating natural habitat in your own backyard by planting native species provides sustainable support for wildlife without the pitfalls of direct feeding.

For those seeking closer wildlife encounters, numerous ethical wildlife viewing tours and programs offer opportunities to observe animals in their natural behaviors with minimal impact, guided by trained professionals who understand how to minimize stress and disruption to the animals.

When Feeding Is Appropriate: The Exceptions

While this article has focused on the dangers of feeding wildlife, there are limited contexts where supplemental feeding can be appropriate when done correctly. Properly maintained bird feeders, when regularly cleaned and filled with appropriate seed mixes, can support native bird populations during harsh winter conditions with minimal negative impacts. Licensed wildlife rehabilitators provide carefully formulated diets to injured or orphaned animals as part of professional care protocols. In some cases, conservation programs may implement carefully managed supplemental feeding for critically endangered species facing severe food shortages.

The key distinction in these exceptions is that they involve careful planning, appropriate foods, and scientific monitoring of impacts—quite different from casual feeding by well-meaning but uninformed visitors to natural areas.

Conclusion

The message “Don’t feed the wildlife” represents more than just a rule to follow—it reflects our responsibility to respect the intricate balance of natural systems. While the impulse to feed wild animals often comes from a place of compassion, true respect for wildlife means allowing them to maintain their natural behaviors and ecological relationships. By understanding the far-reaching consequences of feeding wildlife, we can make more informed choices that genuinely support conservation.

The next time you encounter wild animals, remember that observing from a respectful distance is the greatest gift you can offer them—the freedom to remain wild.